Article

Social Location and Systems of Oppression

Written by Tanya Hannah Rumble

How can we better understand how our identities influence how we see and experience the world? And what does this have to do with discrimination and the impacts of bias? Understanding our own social location is foundational to understanding how individual and systemic bias/discrimination operate. And it is only when we can recognize these impacts, that we can intervene and take action to address them to create healthier and more equitable relationships, organizations, and systems. Here, we begin to unpack three steps in this work:

- Understanding our social location

- Understanding individual and systemic bias and discrimination

- Disrupting bias in ourselves and with others

Understanding our Social Location

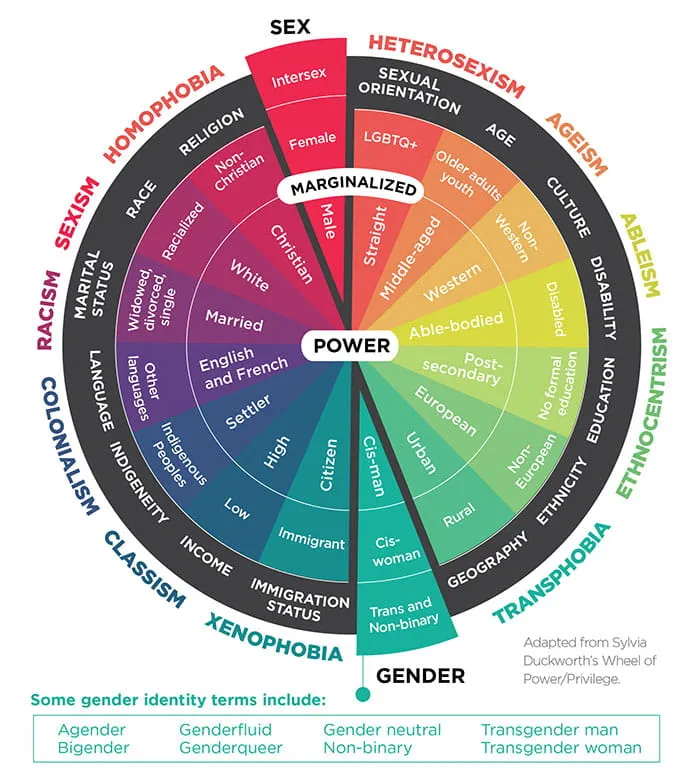

Understanding our social location means understanding how elements of our identity — i.e. gender, race, class, sexuality, etc. — relate to people around us. This can be conceptualized as relational status, position in society, privilege, and/or oppression/marginalization, depending on which element of your identity is at play. Knowledge of our social location helps us reflect on the context in which we exist, and how these elements intersect within ourselves and with others, impacting perception, actions, and relationality.

Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality’ to describe how our individual characteristics intersect with each other and overlap, describing it as “as lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other. We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality or immigrant status. What’s often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts.”1

Activity

- Have you ever plotted your social location?

- Take a few minutes to do this now by reviewing each section of this wheel representing intersectionality and consider within each dimension how close the identity you hold is to power (center of the wheel) or furthest away from power.

- What did you notice as you plotted your social location?

- How much do you know about the different dimensions?

Understanding individual and systemic bias and discrimination

Understanding our social location helps us have a stronger understanding of ourselves and why we see the world the way we do — it also creates space for understanding and empathy when we can recognize both the commonalities and disparities in how others with different identities, status, power, and privilege are experiencing the world. This then, allows us to recognize individual and systemic bias and discrimination. How are our unconscious attitudes impacting how we relate to others, and how we make decisions? How do these biases play out at the individual level, institutionally and system-wide, and when do they lead to discriminatory practices?

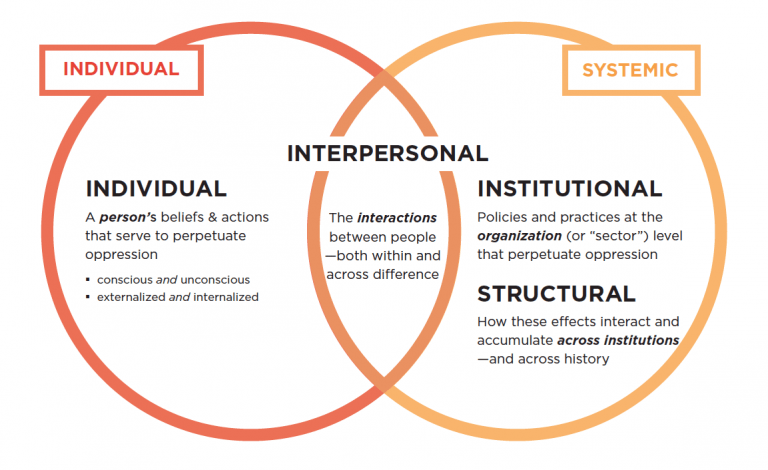

Figure 1. Source:

nationalequityproject.org/frameworks/lens-of-systemic-oppression

- Recognizing and addressing biases is an ongoing exercise that needs to be completed on multiple levels in order to be effective. As the diagram shows, discrimination and bias exist personally, in interpersonal interactions, within our institutions and structurally across institutions (see Figure 1)

- The biases are upheld and strengthened by the interaction of the four systems if not addressed simultaneously and consistently across all four levels

- Example in practice: Individual acts of racism have a pervasive influence on the policies and cultural norms in workplaces such as hiring for ‘fit’ or expecting professional development outside of working hours

One way that individual oppression impacts people from marginalized backgrounds is through microaggressions.

“Microaggressions are the everyday slights, indignities, insults, put-downs, and invalidations that people of color experience in their day-to-day interactions with well-intentioned individuals who are unaware that they are engaging in an offensive or demeaning form of behavior.”

– Dr. Derald Wing Sue, 2007

Common examples of microaggressions include, “I believe the most qualified person should get the job,” signaling that someone is being given an unfair advantage because of their race, or “Your English is so good — where are your parents from?” signaling that people with English as a second language are generally less capable of speaking English.2

Disrupting bias in ourselves and with others

Once we have more knowledge and understanding of our own identities, how they relate to individuals and the systems we are part of, it is essential to apply that knowledge and translate it into action. Here are suggestions on how to practice this action at four levels of relationality:

1. Personal

- Acknowledge we have much to unlearn

- Continually educate ourselves

- Remove guilt/shame/fear as motivator for action

2. In Relationship

- Apologize (‘Ouch’ / ‘Oops’ approach or use other phrases to disrupt)

- Focus on the impact not intention

- Commit to change

3. Interpersonal

- Validate the experience

- Listen and provide support

- Ask how you can help – listen, challenge, validate

4. Organizational

- Be vigilant about group dynamics

- Speak up by calling in or calling out

- Normalize the conversation around how oppression shows up on a regular basis

Additional Resources

For more information visit:

1 time.com/5786710/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality/

2 hbr.org/2022/05/recognizing-and-responding-to-microaggressions-at-work

This article was developed as part of CICan’s 50 – 30 Challenge Ecosystem partnership with ISED. Interested in learning more? We encourage you to visit our website for resources, personalized one-on-one support and training to support your organization on their EDI journey. Keep up to date by signing up for our mailing list.